Jacqueline de Jong is perhaps best known for her affiliation with the leftist Situationist International, for which she edited the Situationist Times between 1962 and ’67, giving particular attention to the wildly spontaneous work of CoBrA. “Imaginary Disobedience,” the Dutch artist’s first solo exhibition in Los Angeles, shifted focus to her own art. Installed in the main gallery and back office of Château Shatto, the mini-overview featured works dating from 1962 to 2016.

Tangled limbs, gaping mouths, and distended anuses jostled for space in the fourteen expressionistic paintings and three works on paper on display. There were interesting formal experiments, from the painted screen Le Salaud et les Salopards (Bastard and Scumbags, 1966) to De achterkant van het bestaan (The Backside of Existence, 1992), a vast sailcloth, suspended from the ceiling, that features a mélange of painted human figures, birds, and monsters dancing across its folds, the fabric’s undulations interrupting the flow of images and demanding that the viewer move around in order to read the piece.

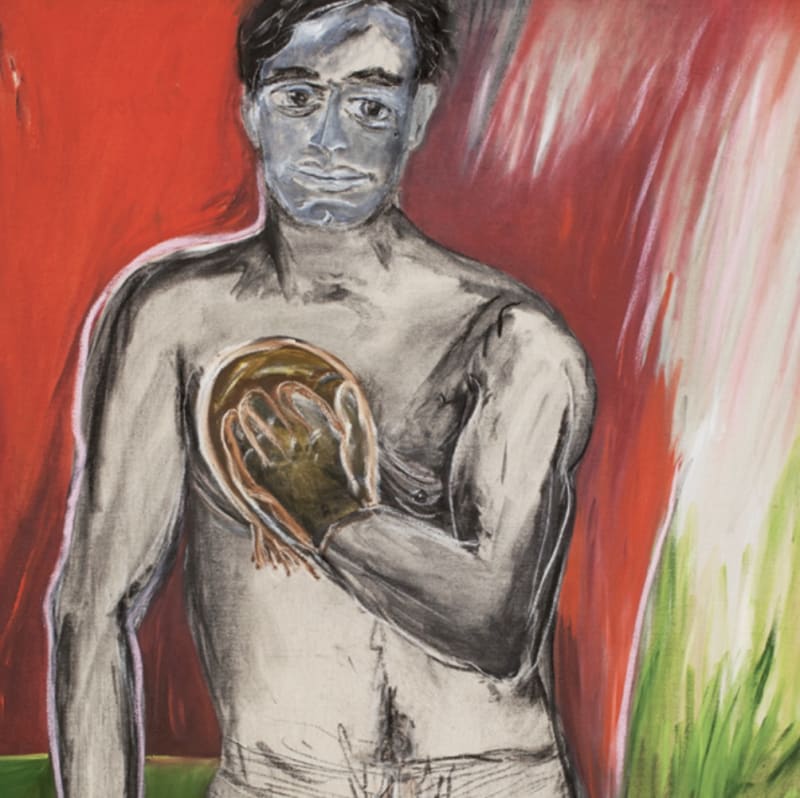

While the forms in 1960s paintings such as Zonnebrand (Sunburn, 1965) approach abstraction, they bear the seeds of the brightly colored, wrenched figuration de Jong would go on to produce. Her exaggerated forms, as in Peeing Hamlet (2012), where an emaciated, four-legged prince crouches while brandishing a grotesque skull, draw comparison to the work of younger contemporaries like Dana Schutz and Nicole Eisenman. De Jong’s paintings look as if they’ve been made at speed. Vivid swaths of color, hastily blocked out, dominate the compositions, bodies are outlined in expansive sweeps of paint, and the ground is often visible between vigorous brushstrokes. This is true right up to the most recent example, Pardonne-moi (Arthur Craven Timide), 2015–16, a portrait of the Dada poet and boxer. The only real departure in the show was Rhapsodie en Rousse (1981), a quasi-naturalistic depiction of an imperious redhead wearing an evening gown, seen in the aftermath of stabbing her androgynous green-robed companion. That this could be a self-portrait prevented the work from being completely out of step with the other pictures, which frequently include portrayals of the artist.

De Jong’s personal touch could be felt most strongly in four diptychs made in 1971–72. The works—each comprising a pair of wood-framed panels joined by a hinge and topped by handles—all feature scrawled diaristic text on the left and colorful illustrations on the right. These paintings have an aleatory, proto-slacker sensibility with their everyday descriptions of meals and phone calls; their multiple dreamlike images of nudes, cars, and sex acts; and trippy titles like After four hours the beans are revealing themselves.

In one diptych, Op het land waar het leven zoet is (In the Countryside Where Life Is Sweet, 1972), de Jong includes, among other details, a pencil-drawn depiction of a group of men who appear to be gang-raping a male figure. Indeed, she seems to characterize love and sex more often as grotesque or violent than as pleasurable. Other works concern themselves with conflict, war, and death. Soldiers pop up repeatedly, most prominently in a World War I–themed trio of works: WAR 1914–1918 (2013), WAR 1914–1918 (2014), and Explosion 1917 (2014). Here, de Jong paints anguished faces, ghostly gas masks, barbed wire, trenches carved into a scarred landscape, and bloody artillery explosions. These images, consistently murky in tone, produce a sense of pain and dread.

That de Jong should dwell so unrelentingly on the dark side of humanity is no real surprise considering her biography. Born on the cusp of World War II to a Jewish family fleeing the Holocaust, the artist lived through an era of unprecedented bloodshed and upheaval, and has remained deeply politically engaged throughout her life. In these works de Jong navigates the relationship between individual base impulses and the broader context of world affairs, illustrating how the former often drive the violent nature of the latter.