There is tension at the heart of the commercial art world. On the one hand, a gallerist will persuade you that art is an investment, and that the work that costs just more than you are comfortable paying will be more loved and valued with each passing year. And on the other hand, gallerists and collectors alike are addicted to novelty. Missing out on the next big thing can provoke adult tantrums.

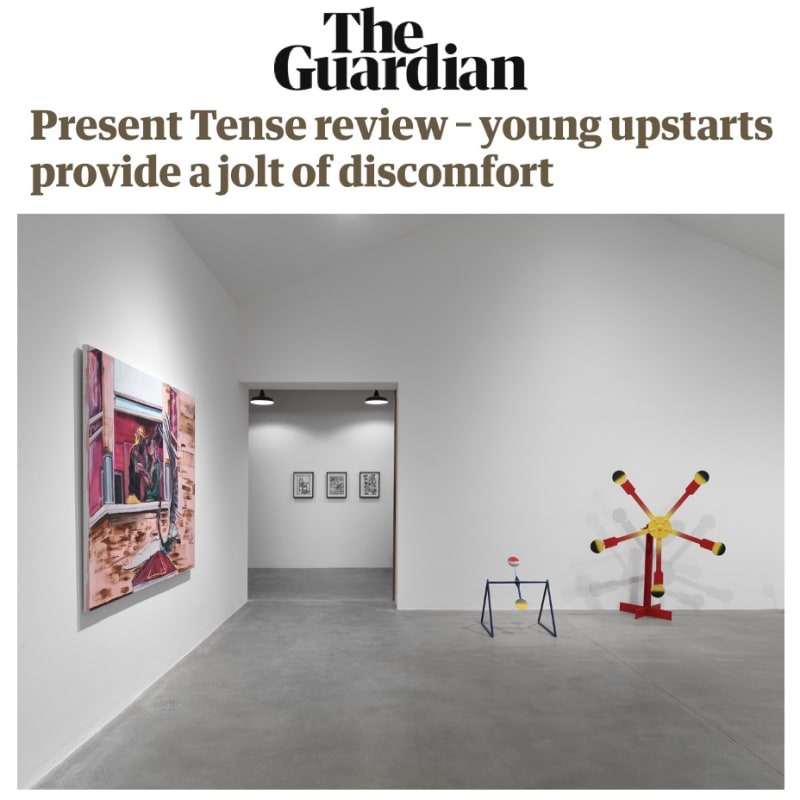

Hauser & Wirth deals in works by legacy names like Louise Bourgeois and Philip Guston, as well as a starry menu of living artists. This season, its Somerset branch is embracing the new with Present Tense, a survey of emerging-ish artists working in the UK. Present Tense suggests something a little edgy, though it’s hard to feel tense in the luxuriant rural sprawl of these day-lit galleries. The art itself is unlikely to scare the sheep: rather than a radical survey of emerging tendencies, this is overwhelmingly an exhibition of figurative painting.

Narrative is evidently back in a big way. Ania Hobson’s figures tower over stylised landscapes and interiors, caught in beams of tawny light as though Eric Ravilious had been let loose in a marmalade factory. In Let the Land Speak (2023) two women huddle conspiratorially in the evening light on the moorland, one caught mid-sentence. A similar pair appear in Wax Top Bar (2023), surrounded by polished wood, raking light and hard minimalist angles. They’re drinking tiny cocktails and shots, wearing expensive looking but unflashy clothes. Hobson has an astute eye for a particular kind of female closeness. It shouldn’t feel so radical to paint young women not performing for the gaze, but instead caught up in moments of friendship.

Shaqúelle Whyte’s urban dramas are caught in a loose, brushy style as though the artist has captured them on the hoof, painting from life as he stares in through the window watching the couple in 1 pence plus 1 pence (2023) engaged in a passionate encounter that could be a dance, a disagreement, a prelude to sex or all three. The urgency of Whyte’s brushwork suggests a chance encounter, but this composition has a surreal edge: the tormented body of a falling swan brushes past the lower edge of the window. A sinister touch, it recalls the fragmenting swans falling across the early paintings of Frank Bowling.

Born in 2000, Whyte is one of the youngest artists here. The oldest, Victoria Cantons, is responsible for the only video in the exhibition, and one of its few genuinely disturbing works. Clinging To My Own Beliefs/ Belly Button Fuzz (2017) shows Cantons face-on, one pearl earring just visible, as she is repeatedly slapped while a voice reads out a list of questions – What is of the skin? What is of old age? What is of impotence? What is of exhibitionism? – and on and on. Cantons starts weeping but stares forward stoically as the blows continue as though she is being brainwashed. Shown beside two large portraits, including the primary-school-uniformed A Transgender Girl (2023), this is an intense engagement with social conditioning and internalised prejudice.

Sculptural works here are likewise concerned with questions of the body and social performance. In Paloma Proudfoot’s striking and silky-toned ceramic reliefs, there is a sense of the body as a construct and technology intertwining with biology. In Laced (2023), one woman winds a bundle of cord drawn from another woman’s veins, while a third woman uses that same cord to lace her into a corset. Commonplace objects like earbuds become part of a network of tech accoutrements that leave the modern body a cyborg mesh of wires and veins. The Ambrosia (2023) sculptures hang like ceramic swings from the ceiling. Bound with belts, these slices of the body present tangles of nerves and eggs – all those roiling anxieties, perhaps, that young women are fed about their fertility.

Within the calm tastefulness of these galleries, Lydia Blakeley’s vivid plasticky paintings of cactus gardens and holidayscapes feel deliciously jarring. Blakey has a keen eye for the markers and textures of taste and deploys them brilliantly. Rendered with the icy detachment of travel brochures, two of her paintings have been stretched on to metal beach loungers, while a live cactus sprouts out of a plastic coolbox filled with crystals. A knowing appeal to our prejudices, the whole arrangement is a refreshing jolt of discomfort in this rural haven to understated wealth.