By Maria Chiara Valacchi,

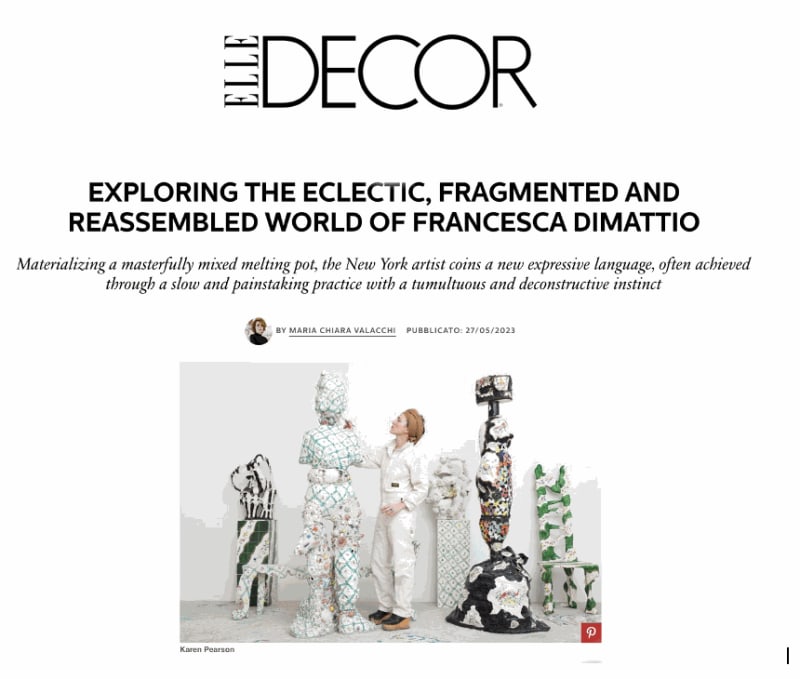

It was 1979 when Niki de Saint Phalle began the project for the Tarot Garden of Garavacchio, in the gorgeous setting of Capalbio, Tuscany. The French artist, inspired by the boundless fantasy of Gaudì, Güell Park, and the various architectural masterpieces she had repeatedly visited in Italy, devoted her body and soul for years to the creation of this magical world of mosaics, fantasies and fetishes, where all her fascinations converged. A burning desire drove her to create an island of peace that could welcome friends and family, contrasting a reality that was changing before her eyes and that was beginning to overlook the importance of the purest things — even beauty — with a vehicle for dreaming. A similar desire seems to move New York-based artist Francesca DiMattio. With long braids and bright eyes, the same pioneering spirit can be found in her sculptural elements, whether clays or precious vases inspired by Chinese porcelain and ancient Greece, large composite sculpture-totems made of stone and resin, or even drapes with various textures. In a game of analysis and re-modulation of culture in its broadest sense, of history and artisanal tradition from the most diverse origins, DiMattio shatters and reassembles a masterfully mixed melting pot from which new and unexpected hybrid forms emerge. It’s a careful combination with which to coin a new expressive language, often achieved through a slow and painstaking practice with a tumultuous and deconstructive instinct. More than mere operations of functional design, the sculptures of Francesca DiMattio are objects imbued with strong identities, programmed to attract us beyond their surfaces and functions. It’s as if, paradoxically, they guard something “alive” within, hoping to burst forth into the space and its inhabitants with their presence.

To find out more, we sat down with the artist for a conversation to better understand her creative eclecticism.

You are a creator of hybrid worlds; fragile and complex at the same time, far from the most refined sense of classicism, while drawing heavily on its many historical references, and still formally authoritative but with a playful patina. Can you tell us about your approach to the subject matter and what inspires you when thinking about a new work?

I look to history for inspiration and structure. I love finding new ways of exploring what’s familiar, whether it’s a Sevres dish or a Roman mosaic. I want to present historical influences in new contexts to see them with new eyes. I perceive each piece as a conversation between different eras and cultures, looking for a formal connection — both in the palette and texture — in an attempt to reduce the space between these very different references. In one piece a beaded motif from an African Yoruba chair sits next to a Turkish Iznick motif. The elements used couldn’t be further apart, but the rhythm of empty white and luminous flowers connects these two distant places instantaneously, breaking down distance and time. For another piece, the blue and white motif from a Ming Dynasty vase sits next to the blue and white motif from a bed sheet to define a visual language capable of crossing history and culture.

You alternate between creating artworks and creating design or fashion objects… among these, is there a world that fascinates you most? How do you govern the differences between these languages?

I’ve always been inspired by the home environment, crafts and decorations; I try to change the adjectives that typically define these things. This has led me to work with a lot of different materials. I try to change the way we’re used to seeing familiar things and to compose them with a new order. A chair wrapped in a plate, a dress wrapped in a vase, a sculpture wrapped in a plate. This disorientation helps us see familiar elements in new ways. I allow myself great freedom to work with different techniques, which I find helps clarify my underlying motivations. Whether I’m making a massive sculpture or a bowl, similar modes of execution unite their creation.

How do you choose a material for your creations and, most importantly, the texture? How do you work with it, technically?

Like paint, clay is incredibly elastic, so it’s still the main material I use. No matter the reference, the weave of a rug, the texture of beads and jewelry, or something smooth and shiny, clay can articulate it. Because there are so many disparate elements at once, it’s important that it’s all made of the same material. When I wanted to make furniture, however, it became clear that clay would not work. I wanted them to be light and easy to move with one hand, so I had to learn how to forge wood overnight. The impetus to make my own works has led me to new places where there’s an urgency to learn new practices and redefine modes of execution. A new material then becomes fundamental to reshape my practice.

Your practice seems linked to a mantric and layered approach… slow in its painstaking execution. How does the competitive and frenetic nature of the city you’ve always lived in — New York — coexist with your patient working process?

There are very different phases in the making of my work. Some are destructive and others are more careful and meticulous. I want every piece to embody both sides. Sculpture allows me to do this because of the different steps involved and the surface treatment that can change the form itself. For smaller works I make various forms such as vases or household objects, sneakers, dish soap or laundry detergent. After carefully rendering these elements in clay, I bend, crush, cut, and push them against each other to build a new whole. After the first firing, I work slowly to glaze the entire piece, often referencing 18th-century French enamel patterns from dishes or decorative objects. The grit and beauty of New York City has been a great inspiration and has surely helped define my aesthetic.