Walking into Pippy Houldsworth Gallery’s new exhibition, BLOODWORK, I had the curious sensation of having travelled back in time. Not particularly far, not to a radically different era, but definitely to a time that has slipped by. The pieces in Zoë Buckman’s solo show were all made this year, but, looking at them, I felt like I had stumbled backwards by about half a decade or so, to the cluster of years when people took photos of themselves reading I Love Dick on the Tube, the internet fell head over heels for Sad Girl Theory, Rupi Kaur posted a photo on Instagram of blood leaking between her legs, and a surprising number of artworks featured milk.

Let me try and explain a bit better. When I was making work for my Art AS Level, I was 16 and had just discovered feminism (bear with me, I promise this is relevant). I read Germaine Greer; I read The Feminine Mystique. In my English classes I wrote essays about madwomen in attics and angels in houses. And, in Art, I cut out women’s bodies from fashion magazines and steadily sewed the bare-breasted bodysuit that graced my copy of The Female Eunuch over their torsos. Later, I ditched the photos, and instead stitched women’s faces onto layers of cloth, before embroidering their cheekbones and eye sockets with bruises made of shimmering, multi-coloured threads and tiny beads.

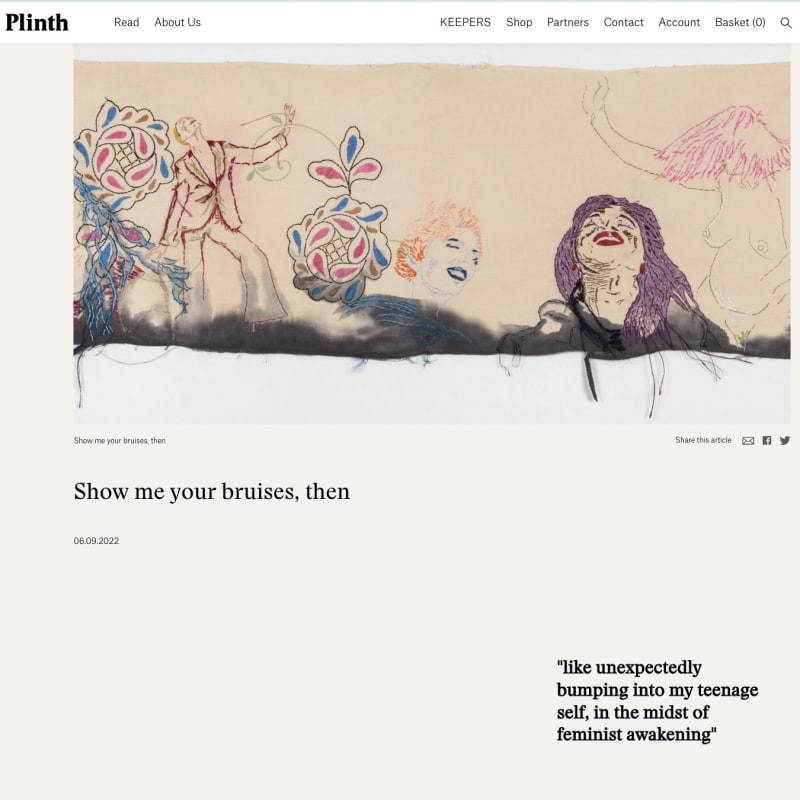

So, encountering Zoë Buckman’s BLOODWORK felt uncanny; like unexpectedly bumping into my teenage self, in the midst of feminist awakening. The first piece, across from the entrance, is a circle of vintage cloth, embroidered with a ring of flowers. Roses spill out from the textile frame, and in the centre Buckman has, in baby pink thread, sewn the lines: “guess i’ll pick up the / bloodwork bill… // & the fucking tip”. Step on from this work, and into the gallery space proper, and you will find more vintage textile pieces, each about the span of an arm. They can broadly be divided into two styles — text-based textiles, which, like the first work in the show, are threaded with emotive poetic fragments (“maybe / i / should / watch my tone”; “his / split-second switch / when consent becomes // abstract // malleable // torn”; “he left with pieces / carved from her / insides / warped // but did not break // she sewed up the edges / exposing the frays”), and portraits of women, their arms thrown up or tongues sticking out, laughing together or smoking alone. Loose threads hang from the delicate fabric surfaces, as if the viewer is being presented with the back of a work – its innards – and, as with the text fragments, the title of each is in lowercase, like Tumblr posts and like Rupi Kaur poems. And, Buckman’s work is in fact based on a poem – the text fragments drawn from a longer work she wrote about domestic and sexual abuse that is now being made public in its entirety in the form of a video work, starring Buckman alongside actresses Cush Jumbo and Sienna Miller, titled Show Me Your Bruises, Then.

Like Buckman herself, all the works are beautiful and elegant and also have a sharp edge to them. The portraits mainly depict Buckman’s social circle, and gesture to their lived experiences of miscarriage, sexual assault, cancer, and going out dancing. They spin around women’s personal pain and their collective joy in equal measure; they are intimate and delicate and yet also seem to yearn towards a kind of universal womanhood, rooted in gendered violence and methods of survival. And, as this yearning hints at, they are also incredibly teenage.

I’m not saying ‘teenage’ in the sense of being underdeveloped, or infantile, but I am saying that there is an adolescent quality to them – an openness and rawness and simplicity that has the effect of feeling like they were all made in a single night, after picking up The Color Purple, or bell hooks’ all about love for the first time. I am also saying that, like the piercing and rollicking emotional register of teenagers, they feel familiar, as if I’ve seen them all before.

Perhaps this is because, in much the same kind of way adolescents help themselves to the grab bag of history and culture in an ongoing attempt to forge a cohesive personality, Buckman’s works seem to be echoes and amalgamations of other, iconic works of feminist art. Judy Chicago’s 1971 photolithograph Red Flag, which depicted a woman’s hand removing a bloody tampon from her vagina. Carole Schneemann’s Blood Work Diary, which she created by drying menstrual blood on tissue paper (supposedly inspired by a former lover’s reaction to seeing a drop of period blood during sex). Louise Bourgeois’s delicate but biting textile works – the cut-up clothes, tablecloths, napkins and bed linens that Bourgeois transformed into intricate renderings of trauma and psychological repair (“I always had the fear of being separated and abandoned,” Bourgeois said of her fabric work. “The sewing is my attempt to keep things together and make things whole.”) Tracey Emin’s quilts; her tent stitched with her sexual partner’s names. Most of all, Buckman’s works seem stitched from the same thread as a near contemporary – New York fibre artist Orly Corgan, who uses vintage fabric and embroidery to create fantastic feminist tableaus. BLOODWORK seems woven from this history of women using domestic and bodily materials to create an alternative artistic canon; a feminist genealogy.

The thing is, in the years between stitching bruises onto cloth and carrying I Love Dick around in various tote bags, my relationship with mainstream feminism has shifted. If it was a glass of milk I might say it has curdled. Tracey Emin has admitted to voting Tory and Germaine Greer’s reputation as a foremost feminist thinker has been undeniably tarnished in the light of recent comments about trans women. I feel like a lot of public-facing feminism has been stolen by TERFs who have no right to use the word, and by ‘Pussy Hats’ and Handmaid costumes, or else by thin, Extremely Online white girls who make money from copying the designs of Black women artists and writing platitudes in curly fonts. Basically, I got tired of privileged white women making feminism all about them; their bodily autonomy, their pain.

So, for a good few years now, when I see work that screams VAGINA, or BLOOD, or WOMEN DON’T OWE YOU PRETTY, I have instinctively recoiled. In 2018, a previous work of Buckman’s that glowed above Hollywood’s Sunset Boulevard — a neon pair of ovaries clad in boxing gloves, titled ‘Champ’ — teetered too close to this for my comfort. But. Four years is a long time in politics. The landscape has shifted. And, in a post-Roe political world, artworks that scream Dilation & Curettage, as one of Buckman’s BLOODWORK pieces does, are both rare in their forthrightness and loaded with new weight. A bunch of red boxing gloves is suspended from the gallery ceiling. “This is my abortion and miscarriage cluster,” Buckman says of the work, and, it is obvious and viscerally true; the gloves hang like clots. Yet, they are covered in Buckman’s recognisable vintage fabrics. There is beauty in them — as with her other textile artworks, Buckman refuses to make the piece wholly representative of violence or pain, but also fights the corner for strength and, yes, joy. For this reason, Dilation & Curettage is, in my opinion, the stand-out work of the show, and exactly the kind of work that needs to be made in and against the current political moment.

BLOODWORK reminded me of my teenage feminist fervour, and it reminded me that battles are not won outright, but fought again and again, in cycles. We now find ourselves at a moment of backlash. And so, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the same symbols and materials and messages are cropping up in today’s feminist art – it feels familiar because the fight is the same.