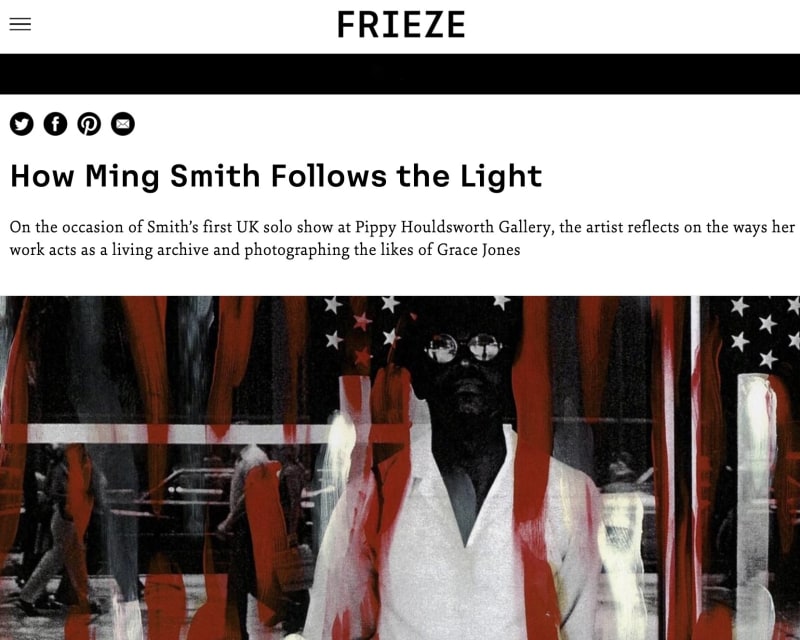

On the occasion of Smith’s first UK solo show at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, the artist reflects on the ways her work acts as a living archive and photographing the likes of Grace Jones

VP: You became interested in photography as a child, when you started to use a Brownie camera that your father had originally gifted to your mother.

MS: Yes, although I never considered myself an artist or a photographer when I was younger. I liked making art because, being shy and self-conscious, it shifted my focus onto the subject I was photographing; I found that very freeing. My goal was to ensure I didn’t make work that was derogatory or void of love and beauty. I wanted to capture encounters in my life, specifically in relation to Black culture.

VP: You were the first female member of the Black photography collective Kamoinge.

MS: When I first came to New York in the mid-1970s, I modelled to make money. One day, I was sitting outside a fashion photographer’s office and I overheard Anthony Barboza talking about whether the medium was a form of nostalgia. My ears perked up. It was there that I learned about Kamoinge and Louis Draper invited me to join. I was the only female member, but I didn’t even think about it at the time.

VP: Your current solo show at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, ‘A Dream Deferred’, includes your portraits of older photographers, such as James Van Der Zee, André Kertész and Brassaï. How did you meet them?

MS: Most of them were chance encounters. I remember that Van Der Zee was such a gentleman, despite having one of the largest and most famous photographic studios in New York. When I went to his apartment to take his portrait in 1979, it was full of furniture – like a storeroom, almost – and you could hardly walk around. I got the sense that the financial struggle of photography was still real for him.

In 1979, Marlborough Gallery in New York held an exhibition of work by Brassaï, and I went because he was my favourite photographer. I was lucky enough to take a portrait of him at the opening, which is included ‘A Dream Deferred’. He placed an umbrella on the desk he was sitting at to make the image more interesting and he was generous with his time. He seemed to recognize that I was an artist, not just someone taking a snap. These little acts of validation kept me going.

VP: You place great importance in your work on shadow, double exposure, light and blur.

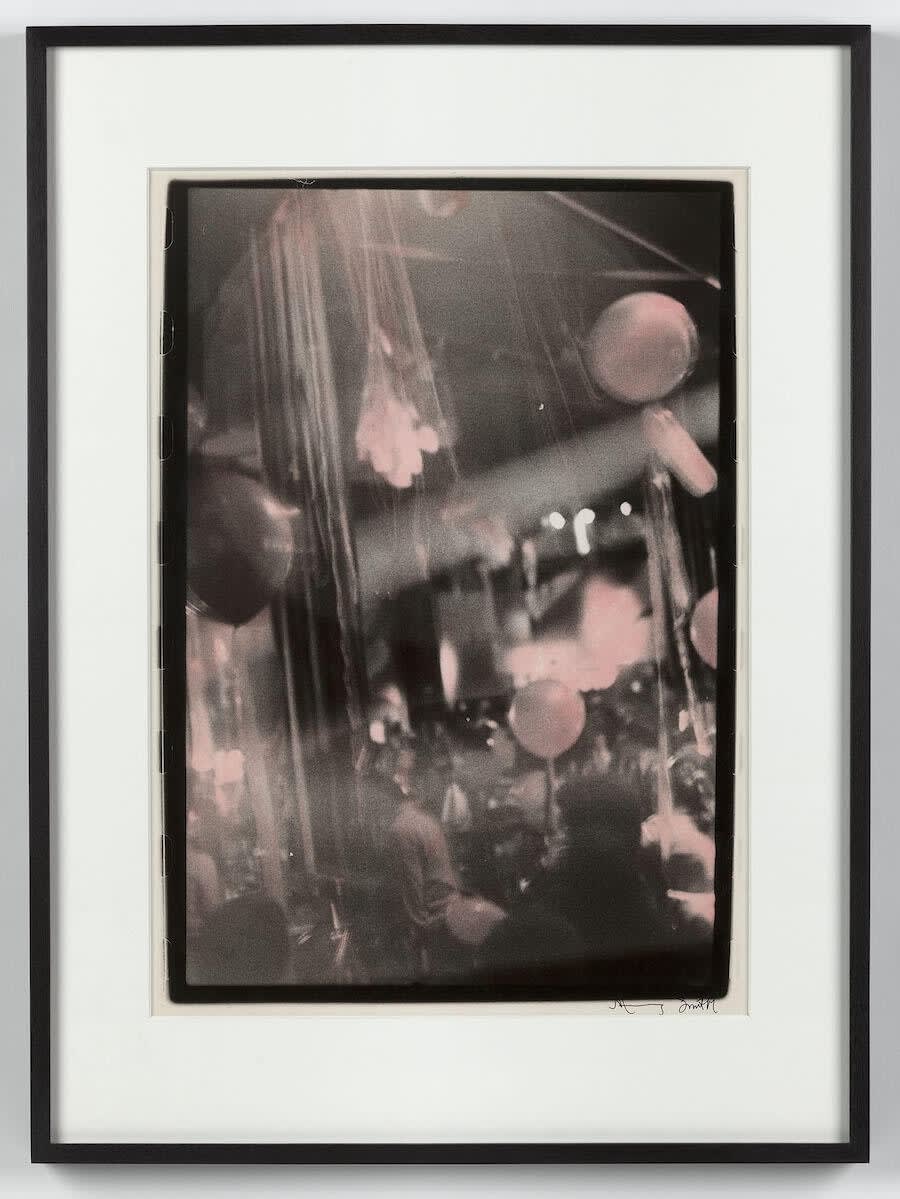

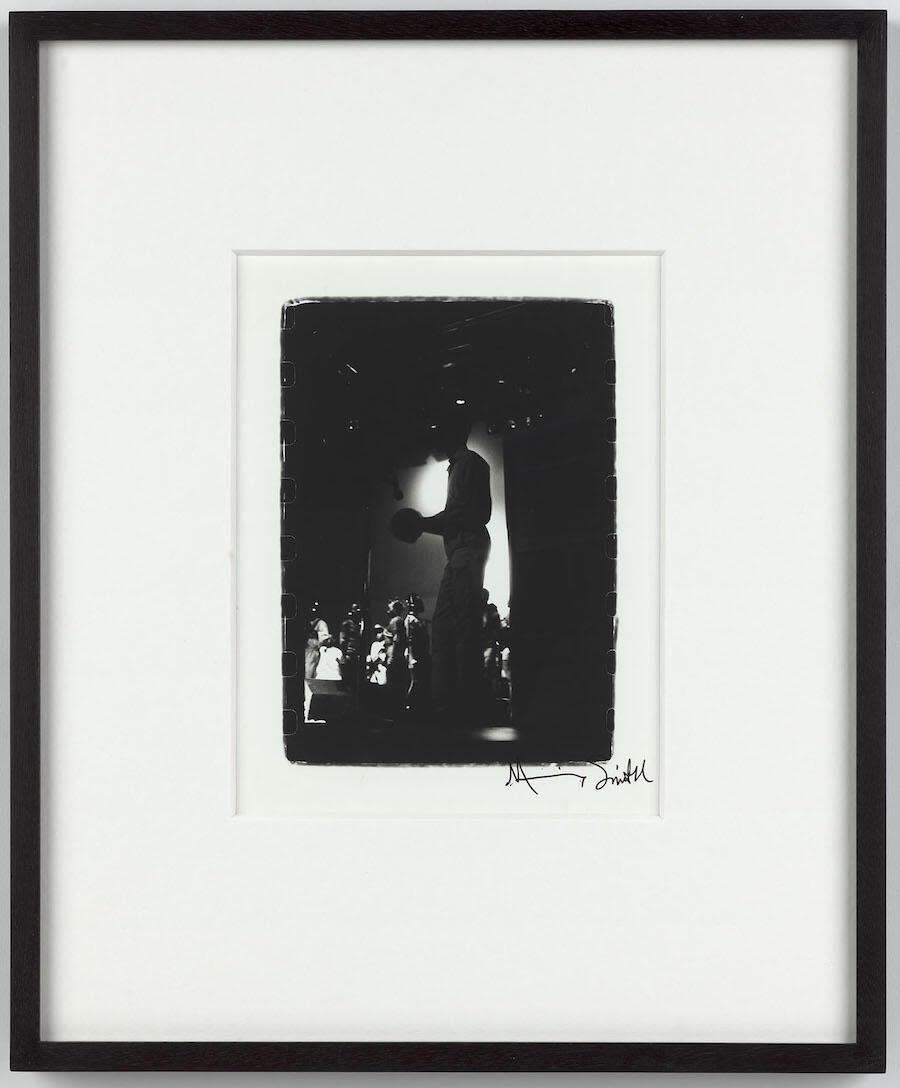

MS: I follow the light. That, to me, is the art of photography – especially street photography, which is not just the subject matter but about improvisation in the moment. I love Brassaï because of how he dealt with light: the shadows, the highlights. Ansel Adams, too. For them, light was the element; they were painting with light.

VP: One of your bodies of work, ‘Invisible Man’ (1988–91), references Ralph Ellison’s book Invisible Man (1952). What influence has literature had on your practice?

MS: Every free moment I had as a young girl, I spent reading or going to the library. My father could recite Shakespeare; my grandmother, who taught English, could recite Paul Laurence Dunbar. All these moments from my childhood influenced my photography. I made a body of work, ‘August Wilson Series’ (1990–94), inspired by August Wilson’s plays and I was also heavily influenced by Zora Neale Hurston. Her work, especially Their Eyes Were Watching God [1937], opened up a whole other world for me.

VP: Music has also been a key influence, and you’ve photographed many musicians, including Grace Jones, Nina Simone and Tina Turner.

MS: Yes. The images are like a diary: they help me to remember. I met Grace in 1973 on a modelling assignment and we had a very personal conversation about what it was like to be a Black model. A couple of years later, I took some photos of her in a ballet outfit [Ballerina (Grace Jones), 1975]. When she did her first performance at Studio 54 in New York in 1977, she called me up and asked me to photograph her. I immediately went over, took the photos, then left. I didn’t hang out with the group afterwards. I was more interested in the photographs than anything else. I got the portrait of Tina Turner because some friends of mine were producing the music video for ‘What’s Love Got To Do With It’ [1984] and they asked me to appear as a backing dancer, so I took her photo.

VP: Your work feels like a living archive.

MS: I like that sentiment. It really is. I was trying to adhere to the highest principles of fine art photography using the elements in my life at the time. My photography is the product of my life.